Non-Avian Dinosaurs Nested in the Arctic, Paleontologists Say

A team of paleontologists from the University of Alaska Fairbanks and Florida State University has uncovered the first convincing evidence that several types of dinosaurs, from small bird-like dinosaurs to giant tyrannosaurs, not only lived in what’s now Alaska during the Late Cretaceous period, but they also nested there.

“It wasn’t long ago that people were pretty shocked to find out that dinosaurs lived up in the Arctic 70 million years ago,” said Dr. Pat Druckenmiller, director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North and a researcher in the Department of Geosciences at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

“We now have unequivocal evidence they were nesting up there as well. This is the first time that anyone has ever demonstrated that dinosaurs could reproduce at these high latitudes.”

Previous studies at a handful of other sites provided tantalizing bits of evidence that one or two species of indeterminate dinosaurs were capable of nesting near or just above the Arctic or Antarctic circle.

Environmental conditions at this time and place indicate challenging seasonal extremes, with an average annual temperature of about 6 degrees Celsius (about 40 degrees Fahrenheit).

There also would have been about four months of full winter darkness with freezing conditions.

“To find out that most if not all of those species also reproduced in the Arctic is really remarkable,” Dr. Druckenmiller said.

Dr. Druckenmiller and colleagues documented the ancient Arctic ecosystem of the Prince Creek Formation in Northern Alaska, including its dinosaurs, mammals, and other vertebrates.

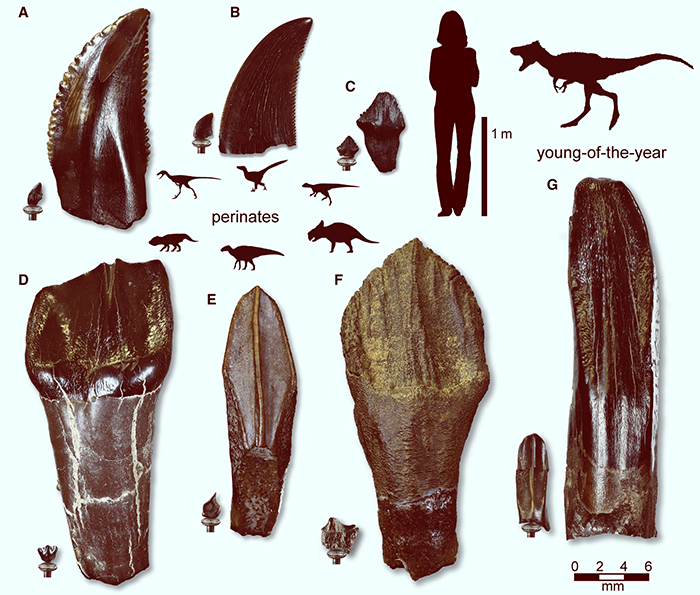

They found hundreds of small baby dinosaur bones, including tiny teeth from individuals that were either still in the egg or had just hatched out.

The types of Arctic dinosaurs include small- and large-bodied herbivorous species including hadrosaurids (duck-billed dinosaurs), ceratopsians (horned dinosaurs and leptoceratopsians), thescelosaurs and carnivores (tyrannosaurs, troodontids, and dromaeosaurs).

“One of the biggest mysteries about Arctic dinosaurs was whether they seasonally migrated up to the North or were year-round denizens,” said Professor Gregory Erickson, a researcher in the Department of Biological Science at Florida State University.

“We unexpectedly found remains of perinates representing almost every kind of dinosaur in the formation. It was like a prehistoric maternity ward.”

Once they knew the dinosaurs were nesting in the Arctic, the scientists realized the animals lived their entire lives in the region.

Their previous research revealed that the incubation period for these types of dinosaurs ranges from three to six months.

“As dark and bleak as the winters would have been, the summers would have had 24-hour sunlight, great conditions for a growing dinosaur if it could grow quickly enough before winter set in,” said Dr. Caleb Brown, a paleontologist at the Royal Tyrrell Museum.

“Year-round Arctic residency provides a natural test of the animals’ physiology,” Professor Erickson said.

“We solved several long-standing mysteries about the dinosaur reign, but opened up a new can of worms. How did they survive Arctic winters?”

“Perhaps the smaller ones hibernated through the winter. Perhaps others lived off poor-quality forage, much like today’s moose, until the spring,” Dr. Druckenmiller said.

Paleontologists have found warm-blooded animal fossils in the region, but no snakes, frogs or turtles, which were common at lower latitudes. That suggests the cold-blooded animals were poorly suited for survival in the cold temperatures of the region.

“This study goes to the heart of one of the longest-standing questions among paleontologists: Were dinosaurs warm-blooded? We think that endothermy was probably an important part of their survival,” Dr. Druckenmiller said.

The team’s paper was published in the journal Current Biology.

_____

Patrick S. Druckenmiller et al. Nesting at extreme polar latitudes by non-avian dinosaurs. Current Biology, published online June 24, 2021; doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.05.041

Source: www.sci-news.com/