10 Terrifying Flying Reptiles

When most people think about prehistoric reptiles, many inevitably think of the lumbering dinosaurs. There’s good reason for that as they were the most dominant life-form on the Earth for over 160 million years (compared to modern humans’ puny 200,000 years) and have captured the imaginations of both children and adults.

One group that is relatively forgotten, however: the pterosaurs. Pterosaurs were not true dinosaurs but rather placed in their own class of flying reptiles. Here we will take a look at 10 of the most bizarre and terrifying pterosaurs.

Ikrandraco avatar

Starting out the list is a unique pterosaur that was only recently discovered and identified in 2014. Ikrandraco is notable for an unusual crest that protruded from its lower jaw. In fact, it is this protrusion that caused paleontologists to name it after Ikran, the flying creature from the movie Avatar, which had a similar lower jaw crest. Crests on the heads of pterosaurs were not uncommon; however, Ikrandraco is the only known pterosaur that sported one on its mandible.

It is believed that the unique lower jaw combined with an expandable throat pouch allowed Ikrandraco to skim the tops of freshwater lakes for fish in what is now China and would have trapped its prey in jaws that contained at least 40 small teeth. Ikrandraco lived in the early Cretaceous period, approximately 120 million years ago.

Rhamphorhynchus muensteri

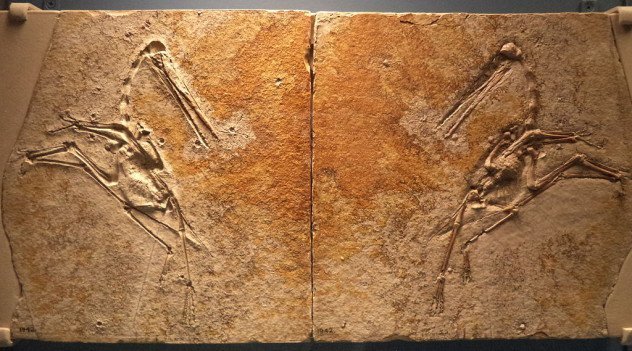

Rhamphorhynchus, whose name means “beak snout,” was a small but fierce-looking pterosaur that lived in the Jurassic period approximately 150 million years ago.

Rhamphorhynchus was small, averaging about 1 meter (3 ft) from wingtip to wingtip, with a long tail ending with a diamond-shaped lobe. It likely skimmed lakes and rivers for fish, catching them in its fearsome tooth-filled jaws.

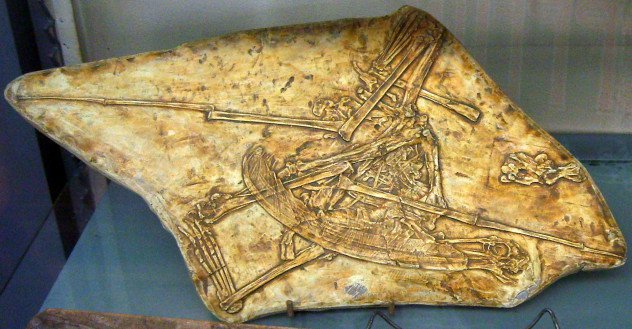

What really makes this pterosaur special, however, is the extraordinary fossils it left behind, with some fossils even showing the outlines of internal organs. One incredible fossil shows what appears to be a Rhamphorhynchus locked in battle with a large prehistoric fish called Aspidorhynchus.

Paleontologists have pieced together the fight from the remains, which shows the large-toothed Aspidorhynchus with its jaws firmly clamped on the wing of the hapless Rhamphorhynchus. Even more amazing is the fact that Rhamphorhynchus has a small fish in its larynx, suggesting that the predator quickly became the prey. Aspidorhynchus likely struggled to swallow Rhamphorhynchus and was unable to expel the pterosaur in its mouth. The deaths of the three prehistoric creatures became immortalized when they sank into the soft sediment, providing paleontologists a rare glimpse into life in the Jurassic period.

Dimorphodon macronyx

While many pterosaurs featured long, graceful heads and necks, Dimorphodon went the completely opposite direction. Looking more like a flying bulldog, Dimorphodon had a short stubby neck on which perched a head and jaw that was much shorter and deeper than many of its pterosaur cousins. Dimorphodon’s head was large for its body, but despite this, was lightly built due to several large openings in the skull.

Dimorphodon was one of the earliest pterosaurs, and it lived in the Jurassic period approximately 176 million years ago. Most early pterosaurs had long tails, and Dimorphodon was no exception. Paleontologists believe the tail was used as a stabilizer while the animal was in flight. It probably used flapping motions to fly, unlike later larger pterosaurs who were primarily gliders.

The limbs were well-developed in Dimorphodon which probably allowed it to move on the ground on its hind legs. Discovered in 1828 by famed British paleontologist Mary Anning, Dimorphodon was the first pterosaur to be found and identified in the United Kingdom.

Jeholopterus ninchengensis

Probably more cute than terrifying, Jeholopterus may have more closely resembled a fuzzy bat than a reptile. Thanks to an extraordinarily well-preserved fossil specimen, paleontologists have determined that Jeholopterus was actually covered in a special type of fiber.

The amazing fossil discovery was made in China and appears to show an adult Jeholopterus that was covered in hair-like fibers. At first, paleontologists thought that they were early forms of feathers known as “protofeathers.” However, they discovered they were actually thick filaments called pycnofibers that differed in structure from mammalian hair. All pterosaurs had them to some degree, but Jeholopterus is the first fossil to conclusively show that they weren’t protofeathers, which directly led to the coining of the term “pycnofibers.”

Jeholopterus probably lived in trees as its claws had a protective covering on them to prevent wear. This shows that it would have been an adept climber as the claws would not wear out quickly. Jeholopterus was a small pterosaur with an approximate 1-meter (3 ft) wingspan and would have fed primarily on insects.

Nyctosaurus gracilis

While many pterosaurs sported cranial crests, Nyctosaurus may have taken home the grand prize for the most impressive headgear. Displaying a massive forked crest that was about two and a half times the length of the skull, Nyctosaurus looked like some Frankenstein mashup between a deer and pterosaur.

It is thought that Nyctosaurus soared the skies above ancient oceans, like the modern-day albatross, feeding on fish and other small marine animals. Nyctosaurus was a moderately sized pterosaur, with a wingspan of approximately 2–3 meters (6–9 ft), but what made it unique was the large crest that paleontologists believe may have been used as a display during mating periods. If this was the case, the crest may have been brightly colored and used to impress females and ward off rival males.

Nemicolopterus crypticus

Contrary to popular belief, not all of the pterosaurs were giants. One only has to look at the diminutive Nemicolopterus to see that the flying reptiles came in all shapes and sizes. This mini-pterosaur only measured 25 centimeters (10 in) from wing tip to wing tip, making it only about twice as large as a modern hummingbird.

Nemicolopterus is among the smallest of the pterosaurs so far discovered, and it is a far cry from its gigantic fish-eating relatives. The tiny reptile had curved toes that it would have used to grip branches in the trees in which it lived. Nemicolopterus likely fed on insects during the early Cretaceous period in what is now China, catching them in its tiny toothless jaws.

Nemicolopterus crypticus, which means “hidden flying forest dweller,” is providing paleontologists with new insight on the lives of inland pterosaurs as well as the evolutionary history of the pterosaurs.

Pterodaustro guinazui

When most people think of pterosaurs, they think of flying creatures snapping up fish and small animals in their large jaws. Pterodaustro is one pterosaur that breaks this traditional line of thinking. Whereas some pterosaurs may have acted like modern-day gulls, Pterodaustro seems to have been the equivalent of a Cretaceous flamingo.

Unlike other pterosaurs that either had long toothless bills or dozens of sharp teeth, Pterodaustro’s jaws were filled to the brim with nearly 1,000 needle-like, modified teeth. Pterodaustro probably scooped up water in its jaws and strained it through these teeth, filtering out small shrimp and other aquatic animals.

Even more interestingly, fossils show that Pterodaustro had a diet similar to modern-day flamingos, which may have caused it to have a similar pink coloration.

Pterodactylus antiquus

There may be no pterosaur more well-known than Pterodactylus, more commonly known as the pterodactyl. This may be due to the fact that Pterodactylus was the first pterosaur to be discovered in 1784, although it was not identified as a flying reptile until years later.

In fact, when it was discovered, scientists believed that Pterodactylus was a sea creature. They believed that the elongated fourth finger that supported the wing structure was actually a paddle used to propel the creature through the water.

Pterodactylus was an early pterosaur that lived in the Jurassic period approximately 150 million years ago. It was a smaller creature, with a wingspan of about 1.5 meters (5 ft), and cruised the skies of what is now Germany. It survived by feeding on fish and other small animals which it captured in jaws lined with nearly 100 sharp teeth.

Pteranodon longiceps

The iconic and arguably most studied of the pterosaurs, Pteranodon is instantly recognizable by the large crest protruding from its head. Living in the Cretaceous period, approximately 85 million years ago, Pteranodon was one of the largest of the flying reptiles with males having wingspans of over 7.6 meters (25 ft). Despite this, Pteranodon was remarkably light with some estimates putting its weight as little as 15 kilograms (35 lb) This is due to a lightweight, hollow bone structure similar to those of modern birds.

Thousands of fossils of this giant have been found throughout North America with the first being described in scientific papers in 1876. Even with this large sample size, paleontologists are still unsure what purpose the large head crest served. Some believe that it may have served as a mating display, as males typically had a larger crest than females. It is believed that Pteranodon fed on fish, but it is not known how it caught them in its large, toothless beak.

Quetzalcoatlus northropi

This terrifying pterosaur is perhaps the one that ruled the skies above all others. Imagine a creature that stands as tall as a giraffe and has a wingspan the size of an F-16 fighter plane. Now imagine that creature cruising the skies above you and you’ll be imagining Quetzalcoatlus.

Named after the Aztec feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl, Quetzalcoatlus dominated the air in the late Cretaceous period, soaring on wings up to 12 meters (39 ft) across. Quetzalcoatlus was probably a glider, using its massive wings to cruise at up to 107 kilometers per hour (67 mph).

Despite these huge dimensions, Quetzalcoatlus could not escape the fate that befell all of the flying reptiles, dinosaurs, and large marine reptiles. A large asteroid eventually wiped them all out approximately 66 million years ago, clearing the way for the new rulers of the sky—modern birds.

Source: www.listverse.com