Diplodocus

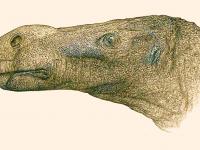

Diplodocus is a genus of diplodocid sauropod dinosaurs whose fossils were first discovered in 1877 by S. W. Williston. The generic name, coined by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878, is a neo-Latin term derived from Greek διπλός (diplos) “double” and δοκός (dokos) “beam”, in reference to its double-beamed chevron bones located in the underside of the tail. Chevron bones of this particular form were initially believed to be unique to Diplodocus; since then they have been discovered in other members of the diplodocid family as well as in nondiplodocid sauropods, such as Mamenchisaurus. It is now common scientific opinion that Seismosaurus hallorum is a species of Diplodocus.

It is mainly thanks to the efforts of one man, the American industrialist Andrew Carnegie, that Diplodocus is now so well known throughout the world. Carnegie, a wealthy man, had a particular interest in dinosaurs, and in the late 1800s and early 1900s, he contributed liberally to the cause of paleontology. he financed many expeditions and excavations and filled his own museum – the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh – with fossil skeletons from all over the United States. When his paleontologists discovered a complete skeleton of Diplodocus, he was so impressed with its size that he commissioned the making of 11 copies of the entire skeleton, which he gave to major museums around the world.

Like other sauropods, the manus (front “feet”) of Diplodocus were highly modified, with the finger and hand bones arranged into a vertical column, horseshoe-shaped in cross section. Diplodocus lacked claws on all but one digit of the front limb, and this claw was unusually large relative to other sauropods, flattened from side to side, and detached from the bones of the hand. The function of this unusually specialized claw is unknown.

Diplodocus’s curious name – meaning “double beam” – is derived from the bones on the underside of its tail, known as chevrons. In most other dinosaurs, these are simple V-shaped elements, but in Diplodocus they are like side-on Ts, projecting both to the front and back. Scientists used to think that, like other sauropods, Diplodocus was a lumbering beast that dragged its tail along the ground. The 1980s, however, brought a renaissance in our understanding of dinosaurs. It dawned on people that, although there was ample fossil evidence of sauropods walking across ancient landscapes, there were never any impressions of tails on the ground. The only conclusion was that the tail must have been held high. However, how an animal of Diplodocus’s weight and dimensions managed this remained a mystery.

Diplodocus is both the type genus of, and gives its name to, the Diplodocidae, the family to which it belongs. Members of this family, while still massive, are of a markedly more slender build than other sauropods, such as the titanosaurs and brachiosaurs. All are characterised by long necks and tails and a horizontal posture, with fore limbs shorter than hind limbs. Diplodocids flourished in the Late Jurassic of North America and possibly Africa.